Whenever I meet someone who grew up on the east coast in the late 70s or early 80s, I ask if they remember Crazy Eddie. I have yet to hear a response other than, “Of course!”

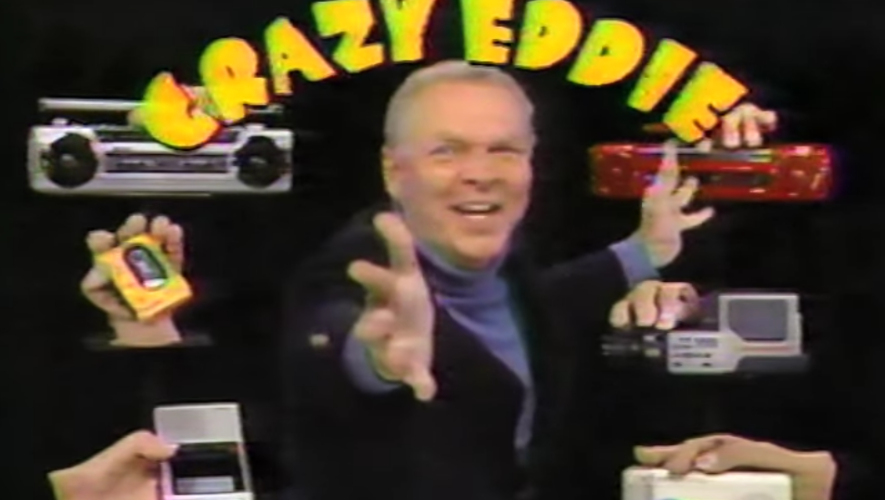

To many, the story of Crazy Eddie is a story of loving to hate a television commercial. The Crazy Eddie pitchman, Jerry Carroll, typically wore a turtleneck under a dark blazer or a Santa Claus suit, sans the fake beard. Carroll waved his arms, would list off electronics merchandise, and scream to “shop around, get the best price, but then GO TO CRAZY EDDIE” because he would beat that price. All the zany theatrics crescendoed into one of the most wily taglines ever to grace the airwaves: “His prices are INSANE!”

The real story of Crazy Eddie is a familiar American story of wild success. It’s about family, business, ambition, money, and betrayal. And, as has frequently been the case in American business, it’s a story of fraud. This particular great American scam is told in painstaking detail by Gary Weiss in “Retail Gangster: The INSANE, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie.” And Weiss, a veteran investigative reporter, has all the receipts, which is far more than could be said of Crazy Eddie.

The real story of Crazy Eddie is a familiar American story of wild success. It’s about family, business, ambition, money, and betrayal. And, as has frequently been the case in American business, it’s a story of fraud. This particular great American scam is told in painstaking detail by Gary Weiss in “Retail Gangster: The INSANE, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie.” And Weiss, a veteran investigative reporter, has all the receipts, which is far more than could be said of Crazy Eddie.

The Eddie in Crazy Eddie is Eddie Antar. Eddie is a streetwise, ambitious kid who builds a chain of consumer electronics stores partly on the campy TV and radio commercials starring Caroll and partly on the willingness to cut corners. A lot of corners. It all began with the nehkdi, or “the skim,” which involved holding onto the sales tax collected on a sale of merchandise. This wasn’t some accounting sleight of hand; the nehkdi was simply how the Antars, Syrian Jews whose ancestors were submitted to endless taxation by Turkish oppressors, conducted business. The nehkdi was distributed throughout the Antar family, piled up in attics and under mattresses, and wasn’t given much more thought. One memorable family story featured Murad Antar—Eddie and Sam’s grandfather and family patriarch who immigrated to America in 1920. On one occasion, Murad was carrying thousands of dollars in cash and thought he was being followed. He ducked into a store, left the money with the Syrian shopkeeper, and promptly forgot about it for several weeks.

Eddie, however, wasn’t satisfied by simply skimming sales tax. He had big plans, but he couldn’t do it alone. His key accomplice was his bookish cousin, Sam E. Antar, known as Sammy. Sammy’s talent for numbers and studious ways made him the perfect person to learn the gray areas of accounting and finance, so Eddie paid for his college education to do just that. This made Sammy indispensable to Crazy Eddie, giving the company a veneer of legitimacy and putting it on a path to rapid growth and fabulous wealth.

Weiss guides us through the cast of characters around Eddie and Sammy. It’s not an easy task. There are at least two more Sams, two Debbies (Eddie’s wife and paramour/second wife had the same name), two Daves, and countless others, including cameos from James Brown, Abbie Hoffman, and yet another Sam: Alito, this time. Weiss keeps it all straight with skill, wit, laying out the intricacies of the fraud and how everyone fits in, wittingly or unwittingly. All the while, 1980s New York City lurks in the background, with all its grit and hustle, a time when those terms weren’t used in corporate slogans.

When Crazy Eddie IPO’d in September 1984, the market responded enthusiastically, with analysts gushing about this scrappy company that was making it big. The stock skyrockets, Eddie and other Antar family members cash in, the company does another stock offering, the stock splits.

But behind the scenes: chaos. To meet Wall Street’s growth expectations, the skim had to give way to bigger, more complicated schemes. Eddie only demanded more when the pressure to grow the company’s revenue intensified. At one point, when he insisted that warehouse managers send their prime merchandise to a wholesaler to artificially increase sales, Weiss makes the priority clear: “The fraud came first.” Meanwhile, Eddie’s personal life is in shambles as he tries to keep money from his wife (Debbie I) with a trail of broken promises, audacious lies, and threats.

The fall of Crazy Eddie in the third act is as spectacular as its rise in the first. It was during this time when the weight of the fraud started crushing everyone, no one more than Sammy. Still, Eddie continues to double down while secretly plotting his escape. The market loses its love for Crazy Eddie, the stock sinks, and the vultures begin to circle. When it becomes clear to Sammy that Eddie is (and always was) looking out for himself, Sammy starts cooperating with the FBI. The dominoes begin to fall, and that’s when Eddie finally absconds to Israel. The law chases him, but Weiss keeps you guessing right to the finish, even if you already know how this story ends.

Founders like Eddie Antar don’t really exist anymore. These days, founders are worshiped as geniuses. They transfix investors with ideas, technology, and charts that go up and to the right. Money, many of them claim, is an afterthought, just a way of keeping score.

Not for Eddie and his crew. Despite the never-ending shenanigans, when you read Retail Gangster, you cannot help but feel nostalgic for businesses like Crazy Eddie, just like we inexplicably yearn for a sleazier Times Square.

Crazy Eddie hawked electronics, ran a hypnotic ad campaign nonstop, and used any accounting gimmick they could. If you had a low price, he would beat it. Simple as that, and today, looking back, we love it. There was no talk of changing the world. There was no vision for the future. There was no keynote filled with yogababble about saving humanity. Why? Because it sounds INSANE.

Retail Gangster: The Insane Real-life Story of Crazy Eddie is now available from Hachette Books

Caleb Newquist is the founding editor of Going Concern and co-host of the podcast Oh My Fraud. Listen on Earmark and earn free CPE.